It’s been three months since the Securities and Exchange Commission’s cyber disclosure rules took effect and rather than creating a deluge of incident revelations, only a trickle has emerged.

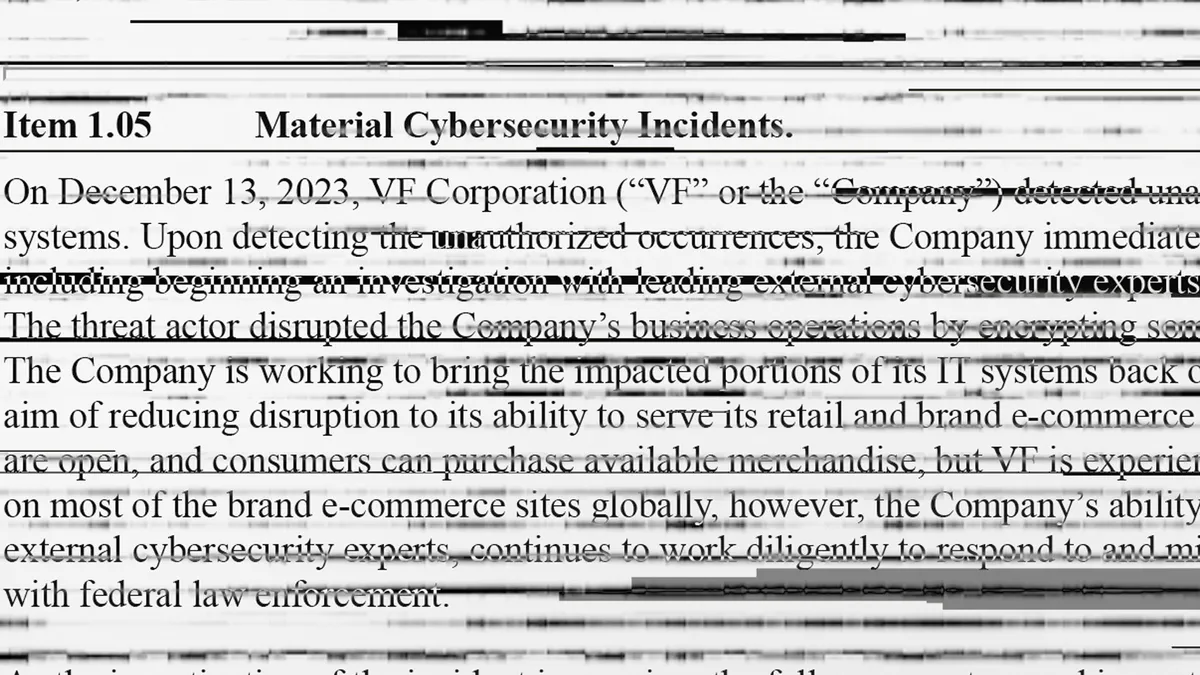

Companies have submitted 12 initial Form 8-K, Item 1.05 filings, the form the SEC began requiring businesses to file for material cybersecurity incidents on Dec. 18. Each of these filings mention an “incident,” and all but two said the activity or access was “unauthorized.”

While the language businesses use in Item 1.05 filings are ultimately crafted to notify regulators and investors of potential risks, these words also signal how a company detects, mitigates, contains and recovers from cyberattacks.

Across the filings Cybersecurity Dive analyzed, none of the businesses described the incident as a breach or data breach in the filing with the SEC — and that was likely by design.

“Words like 'breach' and 'data breach' have very specific legal meanings and consequences, and they also have a particular meaning within what I’ll call the public consciousness,” said Travis Brennan, partner and chair of the privacy and data security practice at Stradling.

“It’s just become a very loaded term, generally, and I think it’s one that companies in these disclosures will studiously avoid using in most cases,” Brennan said. “Once there has been a breach, as opposed to merely an incident, that suggests that the risk of harm has just gone up a few notches.”

The SEC describes a “cybersecurity incident,” in the Federal Register, as “an unauthorized occurrence on or conducted through a registrant’s information systems that jeopardizes the confidentiality, integrity or availability of a registrant’s information systems or any information residing therein.”

The SEC’s definition serves as an umbrella for all manner of cyberattacks.

Implications of oversharing

Businesses often use mild language to limit doubts about their ability to respond and potential legal liabilities, at least early on in the investigation.

This isn’t the case for every disclosure. Five of the companies said data theft or exfiltration occurred. Two businesses described encrypted data or systems.

While companies are leaning on the SEC’s terms to describe cyberattacks, many businesses are sharing information beyond what’s mandated.

VF Corp., Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Microsoft and UnitedHealth Group are outliers among the companies that disclosed security incidents and opted to disclose additional details. They included information about the potential attack vector, the threat actor’s likely identity or motivations, possible or confirmed data theft, and impacts on specific operations or systems.

“The SEC has been clear that a company does not need to disclose specific or technical information about its planned response to the incident or its cybersecurity systems in such detail if it would impede the company's response or remediation of the incident,” Andrew Heighington, CSO at the webcam technology company EarthCam, said via email.

Additional details can convey whether an organization detected an intrusion and responded to the challenge quickly with well-defined remediation steps, containment and recovery.

“One of the biggest cons of sharing a lot of detail is that it potentially puts you at more risk of a copycat attack,” Brennan said.

But businesses have to weigh that against the potential confidence they can channel by describing their incident response or cybersecurity risk management process in a positive manner, he said.

“In instances where we see relatively more details sooner rather than later, it might be because the particular attack vector used is a known one, or a common one,” Brennan said.

Disclosures in dribs and drabs

The SEC rules leave some wiggle room for companies to disclose a cyber incident with a few details, so long as businesses follow up with additional disclosures as more information is gathered.

When companies share more data and analysis in these SEC disclosures, shareholders and affected parties are likely to consider if the business could have easily prevented the incident altogether, according to Amy Chang, senior fellow of cybersecurity and emerging threats at R Street Institute.

Early oversharing compels stakeholders to consider the likelihood of potential poor security controls, a mishandled detection or response, third-party supplier involvement or some other cause, Chang said.

“It is possible that the companies may want to reveal as little detail as possible, or because it is a way to broadly classify the incident as they're continuing to uncover more details about it,” Chang said via email.

The dozen SEC cyber incident disclosures to date are not voluminous enough to draw broad conclusions about organizations’ reporting strategies. But these filings do emphasize the challenges businesses confront and decisions they make in describing cyberattacks to hypercritical and discerning audiences.

“In the early days of complying with the SEC's new cyber rules, we're seeing companies wrestle with balancing the SEC's material cyber incident disclosure requirements in the fog of an incident where there can be significant unknowns,” Heighington said.

“In many instances, companies are disclosing that an incident has occurred, but they are having challenges quantifying the material scope, nature, and impact on not only the business, but also vendors, the company's reputation, and its customers.”