New federal legislation that aims to set cybersecurity standards for healthcare organizations is needed, but many hospitals will likely require more funds to bring their defenses into compliance — and maintain those improvements, experts say.

The Health Infrastructure Security and Accountability Act, introduced by Sens. Ron Wyden and Mark Warner last month, would direct the HHS to develop minimum cybersecurity standards for providers, health plans, claims clearinghouses and business associates, including stronger requirements for systemically important entities and those deemed key to national security.

It also would require covered entities to conduct annual security risk audits and provide funds to hospitals to help them adopt cybersecurity practices. The bill was referred late last month to the Senate Committee on Finance for consideration.

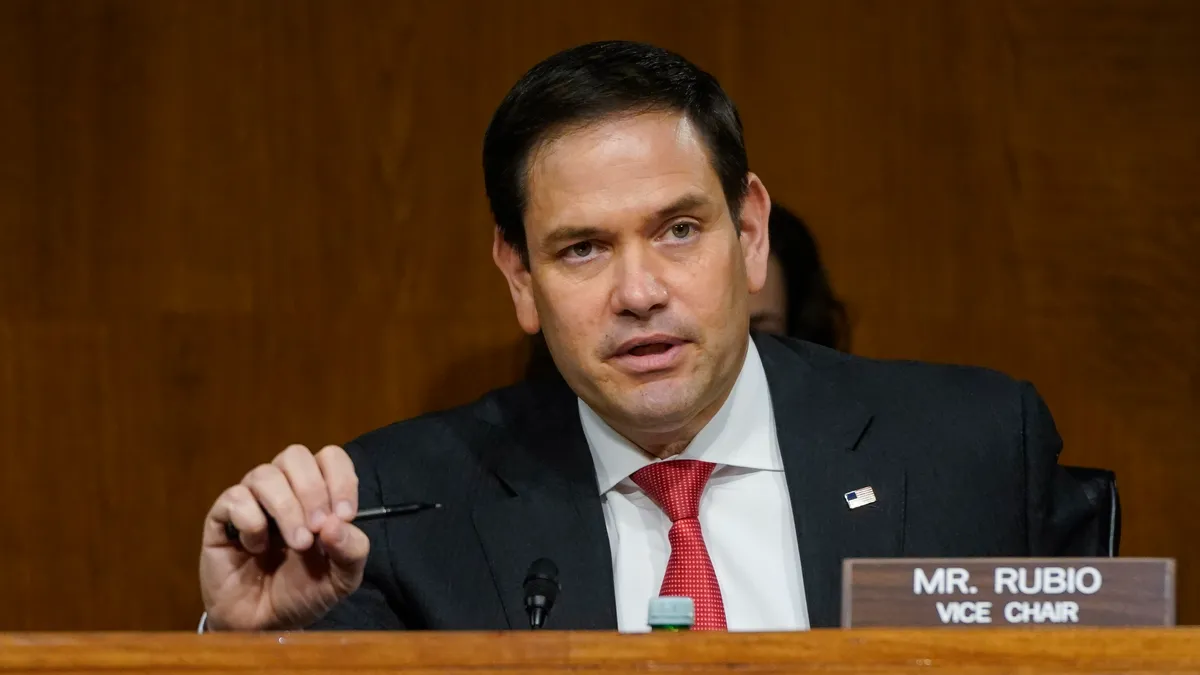

“With hacks already targeting institutions across the country, it’s time to go beyond voluntary standards and ensure health care providers and vendors get serious about cybersecurity and patient safety,” Warner said in a statement when the bill was released.

Experts say the bill is a good starting point to boost cyber preparedness, especially because the healthcare sector is often vulnerable to dangerous attacks.

“We can’t really just let the whole industry do what it wants to do,” said Steve Cagle, CEO of healthcare cybersecurity firm Clearwater. “It’s a bit of the Wild West.”

‘A little drop in the ocean’

The legislation would allocate $800 million over two years for 2,000 rural and urban safety-net hospitals to adopt essential cybersecurity standards. It would also provide $500 million to incentivize all hospitals to follow enhanced cyber practices.

But those funds likely won’t be enough for all hospitals to adopt and sustain cyber improvements, said David Chaddock, managing director in consultancy West Monroe’s cybersecurity practice.

“That will be a little drop in the ocean,” he said.

The problem is that cybersecurity isn’t an issue that requires just one investment — it’s an ongoing practice that needs a host of personnel, Cagle said.

Finding workers could be challenging. Cybersecurity talent is already in shortage globally, and salaries at health systems often can’t compete with compensation in other sectors that are also on the hunt for cyber workers.

Under-resourced hospitals likely won’t have the scale to attract an experienced cybersecurity leader, and may need to outsource their cybersecurity programs to an outside provider to keep up, Cagle said.

That can be difficult to fit into their budgets, especially when hospitals have other needs to contend with, like new equipment or nurse staffing.

Some small hospitals employ just one or two people in their IT departments in total, compared with dozens of personnel dedicated to security alone at larger health systems.

Monitoring for threats, detecting suspicious activity, responding to potential attacks and patching vulnerabilities in hospitals’ technology systems is a 24/7 job, needed 365 days a year, Cagle said.

And that doesn’t include other key work, like policy and procedure writing, technical testing and risk analysis.

“These are the basic, essential things we have to have. It’s multiple people, and it’s multiple skill sets,” Cagle said. “Money is going to help them. [But] you’re not going to give them enough people.”

More prescriptive cyber assessments

HIPAA has long been the go-to law when it comes to healthcare privacy and security, said Melissa Crespo, a partner at law firm Morrison Foerster.

But the law was enacted in 1996, a different era when it comes to healthcare technology. Even when Crespo began practicing years later, most data breaches were related to lost laptops or paper records, not ransomware attacks supported by hostile nations.

HIPAA also requires covered entities to conduct security risk assessments, but it’s a more general framework and organizations can conduct the reviews internally, Crespo said.

The latest bill would be much more prescriptive, requiring healthcare organizations to document an independent security risk analysis, develop a recovery plan in case of attack and conduct a stress test of their capabilities on an annual basis.

The company’s CEO and CISO will have to confirm their company is in compliance, and they could face fines or prison time if they knowingly submit false documentation about their cyber posture or willingly fail to submit their report.

That liability could push some potential leaders to avoid those roles, Crespo said.

“It is a double-edged sword, because I think it will potentially scare off a lot of people that may have actually otherwise been really strong security advocates for an organization from that role,” she said. “But at the same time, it kicks up the burden and the obligation to comply and the need to get it right.”

The HHS will also take on new oversight responsibilities. The bill would require the agency to annually audit the data security practices of at least 20 covered entities or business associates, chosen based on their systemic importance, complaints about their practices and previous history of violations.

Some of those decisions could be made based on priority and service territory, which might put a focus on East Coast hospitals near government facilities, West Monroe’s Chaddock said.

It’s an additional burden on both healthcare organizations and the HHS, experts said. But the industry is no stranger to heavy regulatory requirements, said Elizabeth Southerlan, partner in West Monroe’s healthcare and life sciences practice.

“Hospitals are so used to dropping everything when [the Joint Commission] arrives and just doing it,” she said. “[...] If it’s not clear what they’re going to have to go through during the audit, then that will be chaos. And if it’s not predictable, then that will be chaos. But hospitals can handle it if they know what’s coming.”