Dive Brief:

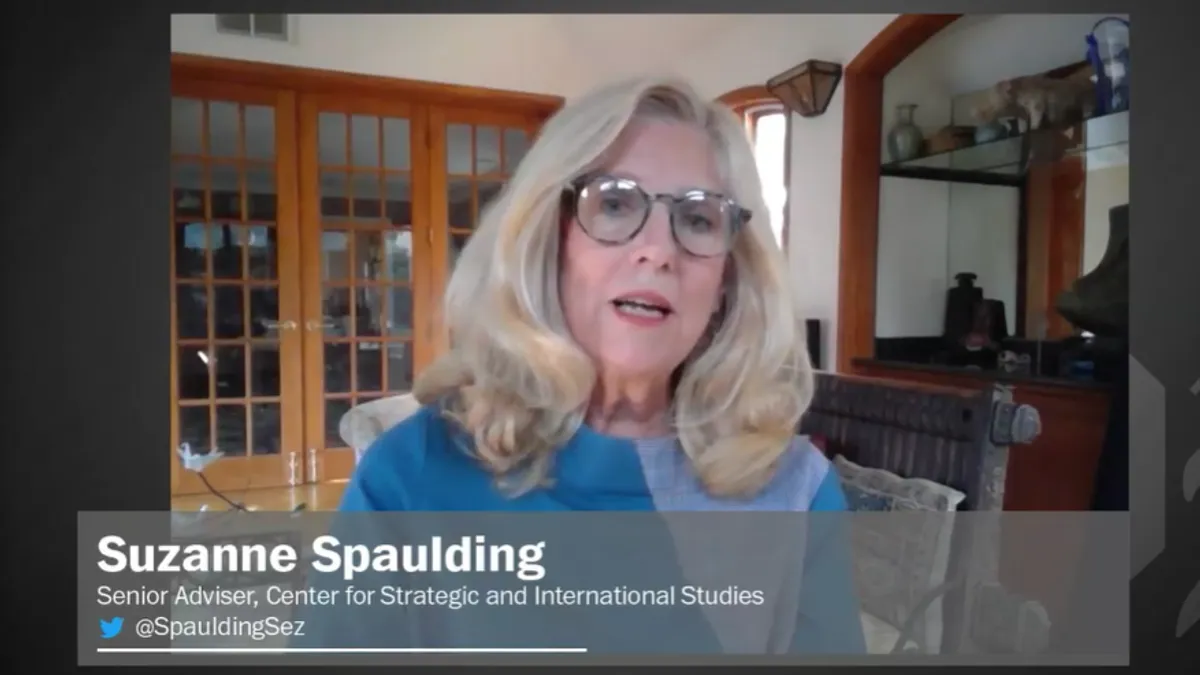

- Regardless of size or industry, "every company needs to understand that they are a potential counterintelligence target," said Suzanne Spaulding, senior adviser for the Department of Homeland Security and director of the Defending Democratic Institutions project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, during a webcast hosted by The Washington Post Thursday.

- Congress and businesses need to "pay attention to" adversaries leveraging U.S. companies for counterintelligence, Spaulding said. "We've seen through a variety of malicious cyber incidents, that no company is too big and no company is too small, to be targeted."

- Given the number of cyberattacks this year, particularly Colonial Pipeline and JBS USA, lawmakers were forced to address cybersecurity because their constituents were directly impacted. While the Colonial and JBS USA attacks were not necessarily espionage campaigns, hackers found weaknesses in U.S. critical infrastructure. And exposed them.

Dive Insight:

While presidents dating back to Ronald Reagan have addressed cybersecurity, Presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden have experienced the bulk of the increase in cyber activity. Biden's first State of the Union address included cybersecurity among one of the crises the U.S. is facing — nuclear proliferation, climate change and a pandemic.

Biden's red line for cybercriminals or nation-state actors is critical infrastructure, but the line was crossed several times this year.

"Once you've got an issue where members of Congress might be asked questions about it at town halls when they go back to their districts or their states — that tends to get the attention of members of Congress and policymakers," Spaulding said. "And I think Colonial Pipeline did that."

Colonial Pipeline was not a household name, though it was made one when the gas pumps closed. For decades, companies in critical infrastructure or owners of industrial control systems (ICS) have benefited from security by obscurity. But the modern digital world no longer allows that.

There are OT/ICS devices in power, water and manufacturing that have long-been excluded from regulatory guidance. That changed in May, after the Colonial Pipeline cyberattack when the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) issued first-ever cyber requirements for pipeline owners and operators.

"Having to line up at gas pumps and pay more for gas is something that hits every American," Spaulding said. But Colonial's ransomware attack "was really a crisis of communication," because the actual supply of fuel was not affected.

It was a lesson in incident response and what messages the public needs to receive. While Colonial's CEO Joe Blount was an active component of the remediation effort — particularly as the liaison between the company and government — the public lacked full understanding of the incident.

People believed the ransomware infiltrated Colonial's OT, assuming that was why the pipeline shut down. The pipeline shutdown was a "stop work" cautionary action to prevent a potential spread of the malware, leaping from the IT to OT environment.

"The American public kind of panicked, and that led to the long lines at gas stations," said Spaulding, which is why a clear and timely response should be prepared as part of incident response.